Dear friends in Christ,

Every age of the Church has its moments of questioning and renewal — moments when hearts seek to rediscover the living truth of the Gospel amid the shadows of human weakness. The story of Protestantism’s origin is one such moment in the long history of Christianity. It was not born out of hatred for the Church, nor simply from rebellion, but from a deep and painful yearning: the desire to see faith return to its first love — to the Word of God and to the grace of Jesus Christ.

When we look back at the 16th century, we find a world of great beauty and great confusion. The Christian faith had shaped Europe for over a thousand years, yet the Church, though rich in spiritual heritage, had become burdened by human corruption, political entanglements, and moral decay. Many sincere believers — priests, monks, and scholars — longed to see the Church purified and the Gospel preached with fresh clarity. Among them arose one man whose conscience would ignite a transformation felt across continents: Martin Luther.

The Seeds of Reformation

Before Luther, others had spoken of reform — John Wycliffe in England and Jan Hus in Bohemia had both urged the Church to return to the authority of Scripture and to moral integrity. Hus paid for his convictions with his life, burned at the stake in 1415, his final words entrusting his soul to Christ. These early reformers sowed the seeds of renewal that would later take root in the hearts of many.

By the early 1500s, the Church in Western Europe faced deep internal tensions. The papacy, once a symbol of unity, had become entangled with political power. The sale of indulgences — promises of the reduction of punishment for sin in exchange for money — scandalized the faithful. Pilgrimages, relics, and rituals often overshadowed the simple message of repentance and faith. The heart of the Gospel — that we are justified by grace through faith in Jesus Christ — seemed clouded by centuries of human addition.

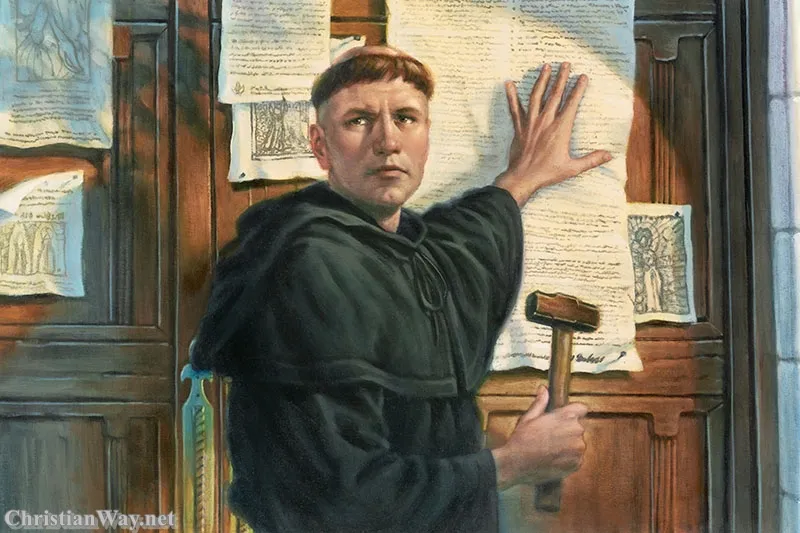

It was into this setting that Martin Luther, an Augustinian monk and professor of theology at Wittenberg, stepped forward with trembling courage.

Martin Luther and the Call to Reform

In 1517, Luther famously nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg — not as an act of rebellion, but as an invitation to scholarly debate. His goal was to call attention to abuses within the Church, particularly the misuse of indulgences, which he saw as undermining true repentance.

Luther’s central conviction was simple yet revolutionary: that salvation is a gift of God’s grace, received through faith in Christ alone. As he studied Scripture — especially the writings of St. Paul — Luther’s heart was set ablaze by the words, “The just shall live by faith” (Romans 1:17). He realized that righteousness was not something earned through human effort or purchased through penance, but given freely through the mercy of Christ.

This rediscovery of justification by faith became the beating heart of the Reformation. For Luther, every doctrine, every ritual, every tradition had to be tested against the unchanging Word of God. Sola Scriptura — “Scripture alone” — became his cry, not as a rejection of Church tradition, but as a reminder that all authority must rest ultimately in the revealed Word of God.

The Spread of the Reformation

Luther’s writings spread like wildfire, carried by the newly invented printing press — a providential tool that allowed the Gospel to reach far beyond university walls. His German translation of the Bible opened the Scriptures to ordinary believers for the first time in centuries, allowing them to hear God’s Word in their own language.

As the movement grew, it found new voices and expressions. Ulrich Zwingli in Zurich emphasized the simplicity of worship and the authority of Scripture. John Calvin in Geneva developed a profound theology centered on the sovereignty of God and the transforming power of grace.

Together, these reformers did not seek to create a new church, but to reform the old one — to call it back to its roots in the Gospel. Yet the divisions that followed were painful. Political powers joined the fray, wars erupted, and Europe’s Christian unity fractured. What began as a movement of renewal became, in part, a movement of separation — a wound that would mark the Church for centuries.

The Heart of the Reformation: Conscience and Grace

At its core, the Protestant Reformation was not merely a historical revolt; it was a spiritual awakening. Luther stood before emperor and bishop, saying the words that still echo through time:

“Unless I am convinced by Scripture and plain reason… my conscience is captive to the Word of God. To go against conscience is neither right nor safe. Here I stand; I can do no other. God help me.”

This was not pride, but conscience illuminated by faith. Luther’s defiance was born of obedience to God’s Word. The Reformation reminded the Church that faith must never be forced, that every soul must stand freely before God, trusting in His grace.

The Reformers emphasized several key truths that continue to shape Protestant faith today:

- Sola Scriptura (Scripture alone): The Bible is the final authority for faith and life.

- Sola Fide (Faith alone): We are justified not by works but through faith in Christ.

- Sola Gratia (Grace alone): Salvation is the gift of God’s grace, not human merit.

- Solus Christus (Christ alone): Christ is the only mediator between God and man.

- Soli Deo Gloria (To the glory of God alone): All of life and salvation exist for the glory of God.

These were not slogans, but spiritual anchors — reminders that Christianity is, at its heart, a relationship of grace between the sinner and the Savior.

The Reformation’s Many Branches

As the Reformation spread across Europe, it took on diverse forms.

In Germany, Luther’s teaching gave rise to the Lutheran Church, preserving liturgical beauty while centering worship on Scripture and the preached Word.

In Switzerland, the Reformed tradition emerged under Zwingli and Calvin, emphasizing simplicity of worship and God’s absolute sovereignty.

In England, the Reformation unfolded uniquely, leading to the birth of Anglicanism, which sought a middle way — via media — between Catholic tradition and Protestant conviction.

And in Scotland, John Knox carried Calvin’s theology into the formation of the Presbyterian Church, rooted in democratic governance and the preaching of the Word.

Thus, from one call for reform arose many communities — each seeking to follow Christ faithfully according to their conscience and understanding of Scripture.

The Catholic Response and the Council of Trent

It is important to remember that the story of Protestantism cannot be told apart from the Catholic response. The Council of Trent (1545–1563), convened by the Roman Catholic Church, became a moment of profound reflection and renewal. While rejecting certain Protestant interpretations, the Council also reformed many abuses within the Church, renewed the discipline of the clergy, and reaffirmed the central role of grace and faith in salvation.

This period — sometimes called the Catholic Reformation or Counter-Reformation — saw the rise of holy men and women such as St. Ignatius of Loyola, St. Teresa of Ávila, and St. John of the Cross, whose deep spiritual lives reminded the Church that true reform always begins in the heart.

Though divisions persisted, both movements — Protestant and Catholic — were, in their own ways, seeking to renew the Church’s witness to the living Christ.

Unity and Division: A Christian Paradox

The Reformation brought both blessing and pain. It renewed the preaching of the Gospel, restored Scripture to the people, and reminded believers of God’s sovereign grace. Yet it also fractured Christian unity, leading to centuries of division and mistrust.

Today, however, many Christians across traditions are rediscovering a deeper truth: that the divisions of the past, while real, do not erase the unity we share in Christ.

In recent decades, dialogue between Catholics, Protestants, and Orthodox Christians has grown. Joint declarations — such as the 1999 “Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification” between the Catholic Church and the Lutheran World Federation — have reaffirmed that much of what once divided us can now be seen in the light of shared faith.

The words of Jesus in John 17 remain the Church’s deepest prayer: “That they may all be one… so that the world may believe that You have sent Me.”

The Spirit of Protestantism Today

In the modern world, Protestantism continues to be a dynamic and diverse expression of Christian faith. From quiet liturgical worship in Lutheran churches to vibrant evangelical movements across the globe, the heart remains the same: a living faith in Christ, rooted in Scripture, sustained by grace, and empowered by the Holy Spirit.

Protestantism has deeply shaped Western thought — inspiring movements for education, literacy, democracy, and human rights — all grounded in the conviction that every person stands equal before God.

Yet beyond all social impact, its greatest gift has been spiritual: the reminder that no church structure, no human priesthood, no ritual can replace the direct relationship between the believer and the Savior who calls each of us by name.

A Closing Word

Dear brothers and sisters, the origin of Protestantism is not merely a story of division, but of awakening — an imperfect yet sincere striving to hear the Word of God anew. It reminds all Christians that the Church must always be reforming — not in doctrine, but in heart, returning again and again to the love of Christ.

The Reformation calls us not to pride, but to humility: to repent of our failings, to cherish the faith we share, and to seek unity in the truth of the Gospel. Whether we worship in a Catholic cathedral, a Protestant chapel, or an Orthodox monastery, the cry of the Reformers still speaks: Christ alone is our righteousness, our peace, and our salvation.

May we, too, in our own time, live this truth — with hearts renewed, with faith unshaken, and with love that bridges every divide.

Reflect and Pray

Lord Jesus Christ,

You are the Word made flesh, the living Truth that sets us free.

Heal the wounds of Your Church, and teach us to walk in humility and love.

May Your Spirit lead all Christians to unity in faith and charity,

That the world may know You and the peace You bring.Strengthen our hearts to live by Your grace alone,

To trust in Your mercy,

And to glorify Your name in all we do.Amen.

— Fr. John Matthew, for Christian Way