Every human soul, in its deepest longing, seeks the image of God — not an idea, not a symbol, but a living presence that can be touched, seen, and loved. In Orthodox theology, this desire finds its fulfillment in Jesus Christ, the Incarnate Word, the visible Image (Eikon) of the invisible God. The Eastern Christian tradition has always guarded this mystery with reverent beauty, where theology and art, prayer and doctrine, merge into a single act of worship. In Christ, divinity and humanity meet — and in the holy icons, that meeting shines forth for all generations.

![]()

The Orthodox Church does not separate what is believed from what is seen. Its theology lives and breathes through its liturgy, its hymns, and its sacred art. And at the center of all these expressions stands one radiant truth: Jesus Christ is God made man, the second Person of the Holy Trinity, who entered history to unite heaven and earth.

The Heart of Orthodox Christology: The Word Made Flesh

Orthodox theology begins and ends with the mystery of the Incarnation. The prologue of Saint John’s Gospel is read with awe and silence: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God… And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:1,14). For the Orthodox believer, this is not merely a statement of doctrine — it is the very heartbeat of the universe.

In this revelation, God does not speak from afar. He enters into His creation, taking on our human nature so that we might share in His divine life. As the Fathers of the Church proclaimed: “God became man so that man might become god,” not by nature, but by grace and participation in the divine life (St. Athanasius, On the Incarnation).

Christ as Perfect God and Perfect Man

The Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD, deeply cherished by the Orthodox Church, declared that Jesus Christ is “one and the same Son, perfect in divinity and perfect in humanity… one person in two natures, without confusion, without change, without division, without separation.”

This balance between divine and human natures is not a philosophical solution but a profound mystery — one experienced in the life of the Church. Every Orthodox hymn of Christmas, every icon of the Nativity, expresses this truth with luminous clarity: that the One lying in the manger is at the same time holding the universe in His hands. The humility of God is the glory of God.

Christ as the New Adam

The Orthodox Fathers often spoke of Christ as the New Adam, who restores humanity to its original beauty. Where the first Adam brought death through disobedience, the New Adam brings life through His obedience unto the Cross.

Saint Irenaeus of Lyons wrote: “As by one man’s disobedience many were made sinners, so by the obedience of one shall many be made righteous.” In Christ, the human story is rewritten — not by erasing the past, but by transfiguring it. His wounds become the gates of resurrection. His death becomes the birth of new life.

Through this new Adam, humanity is no longer a tragedy but a promise fulfilled. The Orthodox believer looks upon the face of Christ and sees not only God but also what humanity was always meant to be — radiant, compassionate, and filled with divine light.

The Theotokos and the Mystery of the Incarnation

No reflection on Orthodox Christology is complete without mention of the Theotokos, the Mother of God. The title itself — affirmed at the Council of Ephesus in 431 — safeguards the truth of the Incarnation: that the One she bore in her womb was not a mere prophet or holy man, but God Himself.

The Orthodox veneration of Mary is not separate from the worship of Christ; it flows from it. Every icon of the Theotokos points to the Child she holds, and every hymn to her magnifies the mystery of divine condescension. As the Church sings, “He whom the whole universe cannot contain was contained within your womb.”

In the Orthodox vision, Mary is not adored but honored as the first and perfect disciple — the one who said “yes” to God in complete freedom. Through her, heaven kissed the earth, and God took on a human face.

The Cross: The Throne of the King

In Orthodox theology, the Cross is not merely an instrument of suffering — it is the throne of glory. Christ reigns from the Cross, not in defeat, but in divine power revealed through love.

The icon of the Crucifixion in the Orthodox Church never isolates pain from victory. Christ is shown not as crushed by agony but as serenely triumphant, eyes open, embracing the world He redeems. This is the paradox at the center of the Orthodox faith: God conquers by surrender, saves by dying, and reigns by serving.

As Saint John Chrysostom proclaimed in his Paschal Homily, which resounds every Easter in Orthodox churches around the world:

“Christ is risen, and life reigns! Christ is risen, and not one dead remains in the tomb!”

In this proclamation, theology becomes praise. The Cross and Resurrection are not two separate events but one single mystery of love — death swallowed up in victory.

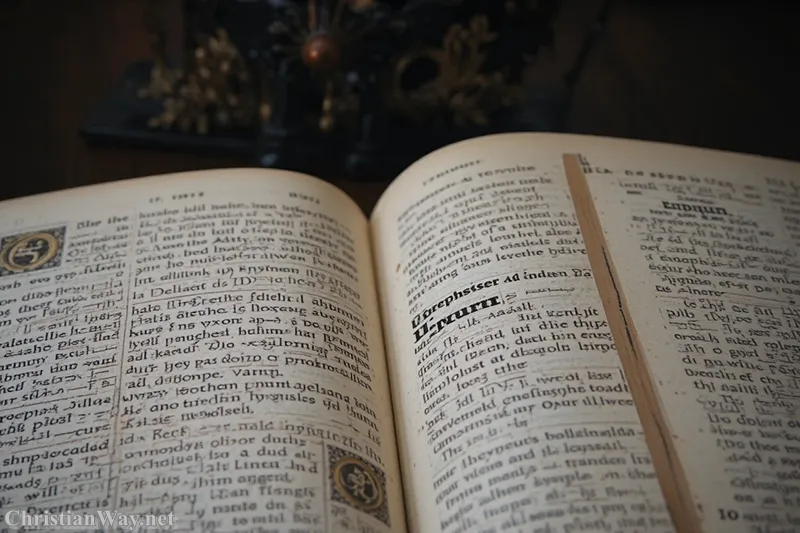

Icons: Theology in Color

For the Orthodox believer, theology is not confined to words — it is also seen and touched. The holy icons are not mere art or decoration; they are theology in color, windows into eternity. Through them, the invisible is made visible without being reduced to mere image.

The Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicaea II, 787) affirmed the veneration of icons precisely because Christ became visible. As Saint John of Damascus wrote: “I do not worship matter, but I worship the Creator of matter, who became matter for my sake.” If God has taken on flesh, then His human face can be painted; His love can be seen through the colors and lines of sacred art.

The Icon of Christ Pantocrator

Perhaps the most central image in Orthodox iconography is that of Christ Pantocrator — the Almighty, the Ruler of All. His face, serene yet penetrating, reveals the mystery of divine majesty joined with human compassion. In His left hand, He holds the Gospel; in His right, He blesses the world. His eyes — one gentle, one judging — reflect both mercy and truth.

This icon is not simply a portrait. It is a confession of faith, a visual proclamation that “Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.” It calls the viewer not to admiration, but to conversion — to behold the face of the One who knows them utterly and loves them still.

The Transfiguration and the Light of Tabor

Another beloved image in Orthodox iconography is the Transfiguration, where Christ’s face shines brighter than the sun. In this event, the apostles glimpsed the uncreated light — the divine glory hidden within the humanity of Jesus. The icon of the Transfiguration teaches that the light of God is not external but radiant from within the purified heart.

In Orthodox mysticism, this same light — the Taboric Light — becomes the symbol of the soul’s union with God. The goal of Christian life, as taught by the hesychasts and articulated by St. Gregory Palamas, is theosis — the transformation of the human person by grace into the likeness of God. As we behold the face of Christ, we are changed into His image.

The Icon as a Meeting Place

To stand before an icon of Christ is to stand on holy ground. It is not an exercise in imagination but an encounter. The Orthodox believer kisses the icon not as an idol but as a living presence — a gesture of love directed through the image to the One depicted.

Saint Basil the Great expressed it beautifully: “The honor given to the image passes to the prototype.” Thus, the icon becomes a bridge between heaven and earth, matter and spirit, time and eternity. It is the visible proof that salvation is not an escape from the world but the transfiguration of it.

Every color, every gesture in an icon is a sermon. The golden background signifies divine light; the absence of shadows reveals the victory of eternity over decay; the elongated faces and serene expressions speak of a world already redeemed. Icons are not naturalistic because they do not depict fallen nature — they reveal nature redeemed.

Christ in the Divine Liturgy: The Living Icon

In Orthodox worship, the theology of Christ and the theology of the icon converge in the Divine Liturgy. The Eucharist is the living icon of Christ’s presence — not painted, but enacted. Here, the faithful enter into the mystery of His death and resurrection, and in receiving His Body and Blood, they become what they behold: the Body of Christ.

In the Liturgy, words, images, and gestures unite to reveal one reality — Christ in our midst. The priest proclaims, “Christ is in our midst,” and the people respond, “He is and ever shall be.” This confession sums up the entire Orthodox faith: that Christ is not a distant figure of history but the ever-living Lord, truly present among His people.

Christ the Victor and the Healer

Orthodox spirituality views Jesus Christ not only as Redeemer but also as Healer — the Physician of souls and bodies. In the resurrection icon, He is shown descending into Hades, breaking the gates of death, and lifting Adam and Eve from their tombs. This is not a metaphor but the proclamation of victory: Christ has entered the darkest places of existence to fill them with light.

The Orthodox believer prays not merely for forgiveness but for healing — therapeia — the restoration of the soul to its original wholeness. In this way, salvation is not only a legal pardon but a living communion, a process of being transformed by divine grace.

Christ and the Journey Toward Theosis

All Orthodox theology converges on one goal: theosis, or divinization. As Saint Peter writes, “We are called to become partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4). Through the Holy Spirit, believers are drawn into the life of Christ, not as spectators but as participants. The entire spiritual life — prayer, fasting, worship, and love — is oriented toward this union.

The image of God within us, darkened by sin, is restored through repentance and grace. The more we behold Christ, the more we become like Him. The icon thus becomes both mirror and prophecy — it shows us not only who God is but who we are called to be.

Reflect and Pray

Dear brothers and sisters, Orthodox theology and iconography together teach us one living truth: that God has a human face, and that face is filled with love. In Jesus Christ, eternity entered time, and the invisible became visible. The icons that surround the faithful in Orthodox churches are not simply art — they are reminders of this wondrous nearness of God. They invite us to lift our hearts, to see not with our eyes alone but with faith, to recognize that all creation is destined to reflect the glory of Christ.

As we gaze upon His face — whether in prayer, in the icon, or in the Eucharist — may our hearts whisper the ancient confession: “My Lord and my God.”

May the light of Christ, shining through the sacred icons of His love, illumine your soul and draw you ever closer to the eternal beauty of His presence.

— Fr. John Matthew, for Christian Way