Welcome, dear brothers and sisters in Christ, to a deep exploration of a life that fundamentally reshaped the landscape of Western Christianity. Today, we turn our gaze toward Pope Saint Gregory VII, a figure known in the world before his elevation as Hildebrand of Soana. His was not a papacy of quiet piety, but one of spiritual revolution. Gregory VII stands as the singular, unwavering champion who dared to restore the dignity of the Church in the face of rampant worldly corruption. He was the man who, armed with nothing but the authority of St. Peter, brought the most powerful secular ruler in Christendom—Emperor Henry IV—to his knees in the snows of Canossa.

As a guiding light for Christian Way, we recognize that his pontificate (1073–1085) was the crucible from which the medieval Papacy, independent and spiritually potent, was forged. He transformed the ideal of papal primacy into historical reality, asserting that the spiritual power held by the successor of Peter was superior to any temporal authority. He faced persecution, exile, and the betrayal of those he loved, yet he died victorious in spirit, leaving us with a final testimony that rings through the ages: “I have loved justice and hated iniquity, therefore I die in exile.” This biography seeks not merely to recount the facts of his life, but to discern the divine providence that positioned this small, determined man as the ultimate architect of Church freedom.

Profile of Holiness

| Attribute | Detail |

|---|---|

| Birth Name | Ildebrando di Soana (Hildebrand) |

| Lifespan | c. 1015 – May 25, 1085 |

| Birthplace | Sovana, March of Tuscany (Modern Italy) |

| Service Period | Pope: 1073–1085 (Preceded by two decades as Papal Archdeacon and Advisor) |

| Feast Day | May 25 |

| Patronage | Diocese of Sovana, Reformers, Defenders of Church Liberty |

| Key Virtue | Unwavering fidelity to Iustitia (Godly Justice) |

The Cradle of Grace: Historical Context & Early Life

The world into which Hildebrand was born around 1015 was one where the seamless garment of the Church was badly frayed by the stains of worldliness. The 11th century was a turbulent era for the Christian faith, defined by a crisis of identity in the Latin Church. Popes were often installed and deposed by powerful Roman noble families or, more worryingly, by the German Emperor, who asserted his right to appoint the Supreme Pontiff. This practice, known as Lay Investiture, infected the entire hierarchy, from the Archbishops of Germany to the parish priests of Italy. Bishops were seen less as spiritual shepherds and more as feudal lords, owing allegiance and military service to the Emperor in exchange for their spiritual office and vast landholdings. This, in turn, fueled two great moral scourges: simony (the buying and selling of church offices) and clerical incontinence (the violation of priestly celibacy), often referred to by the reformers as “Nicolaitism.” The Church was rich in land and poor in spirit.

Hildebrand hailed from humble, though respectable, origins near Sovana in Tuscany. His father, Bonizo, was perhaps a modest artisan or farmer. Crucially, his path was set when he was sent to Rome as a boy for education. While earlier hagiographies, seeking to link him to the great traditions of monasticism, suggested he became a monk at St. Mary on the Aventine, modern scholarship suggests a more likely scenario: he was educated in the rigorous, communal lifestyle of the regular canons at the Lateran, dedicated to the vita apostolica (apostolic life). It was here that he was profoundly influenced by his uncle, and most importantly, by John Gratian, who would later become Pope Gregory VI. When Gregory VI was forced into exile in 1046 by Emperor Henry III, Hildebrand, though only a young cleric, chose to follow his master into Germany, demonstrating an early, deep sense of loyalty and a willingness to suffer for the cause of a rightful—albeit deposed—Pope.

This period of exile was formative. While in Germany, Hildebrand spent time at the great Benedictine Abbey of Cluny in France, a powerhouse of ecclesiastical reform and a bastion against simony and secular control. This experience cemented his conviction that the Church’s survival depended entirely upon its freedom from secular interference and its adherence to the highest moral standards. When the reforming Pope Leo IX called him back to Rome in 1049, Hildebrand returned not just as a student of the Church, but as a seasoned revolutionary ready to wage war for the purity of Christ’s Bride.

The Turning Point: Vocation and Conversion

Hildebrand’s “conversion,” in the sense of a sudden break from sin, was not dramatic like that of St. Augustine, but rather a slow, relentless turning toward the absolute pursuit of ecclesiastical righteousness. His vocation was one of service, deeply rooted in administration and the correction of institutional wrong. The call of God came to him not in a blinding flash, but in the relentless, grinding work of the papal bureaucracy. He was initially appointed by Pope St. Leo IX as Cardinal-Deacon and Papal Treasurer—a crucial role that allowed him to clean up the notoriously corrupt papal finances and acquire deep knowledge of the Church’s temporal affairs.

For nearly twenty-four years (1049–1073), Hildebrand served as the indispensable chief counselor and archdeacon to five successive reforming Popes. During this period, he was, in effect, the hidden engine driving the nascent reform movement. He orchestrated the critical Papal Election Decree of 1059, issued under Pope Nicholas II, which removed the right of imperial and Roman aristocratic participation, granting the sole power of electing the Pope to the College of Cardinals. This was a pivotal move, a legislative declaration of independence that laid the groundwork for his own eventual papacy.

The obstacles that stood in his way were not internal doubts, but the entire entrenched system of feudal Europe. His struggle was external: he faced the opposition of powerful bishops who had bought their sees, priests who had married, and emperors who felt their God-given authority was being usurped. His true moment of turning came on April 22, 1073. As the funeral rites for Pope Alexander II were being conducted in the Lateran Basilica, a sudden, tumultuous cry erupted from the clergy and the Roman people: “Let Hildebrand be Pope! Blessed Peter has chosen Hildebrand the Archdeacon!” This acclamation was an extraordinary, almost revolutionary, act—a direct violation of the 1059 decree he himself helped author, which required a formal election. Hildebrand resisted, reportedly fleeing the scene, but he was found and forced to accept the mantle. He was consecrated on June 29, 1073, and took the name Gregory VII, in honor of his mentor. This moment was the final, irreversible turning point: the skilled administrator was suddenly catapulted onto the Chair of St. Peter, compelled by the voice of the Church to execute the radical reform he had spent decades planning. The spiritual struggle now became a military and political contest for the soul of the West.

The Great Labor: Ministry and Mission

The pontificate of Pope St. Gregory VII was dedicated entirely to The Great Labor—the restoration of libertas Ecclesiae (the freedom of the Church). His work is encapsulated in the movement known to history as the Gregorian Reform. His ministry was not defined by quiet diplomacy but by authoritative decrees and unwavering confrontations. He immediately focused his energies on the three pillars of corruption: simony, clerical marriage, and the greatest threat of all, Lay Investiture.

In a series of Lenten Synods in Rome (1074, 1075), Gregory issued decrees that were nothing short of revolutionary. He declared that any cleric who accepted a church office from a layman, and any layman who presumed to grant one, was automatically excommunicated. This decree directly challenged the power base of virtually every monarch and noble in Europe, particularly the young and ambitious Holy Roman Emperor, Henry IV. Henry IV continued to invest bishops, treating the Pope’s decree as a mere suggestion. Gregory responded by sending the Emperor a scathing letter, reminding him that the priesthood was higher than the kingship, citing Christ’s words to Peter: “Feed my lambs, feed my sheep” (John 21:15–17).

The conflict reached its terrifying climax when Henry IV, rallying German bishops at the Synod of Worms (1076), declared Gregory deposed, citing the irregular nature of his acclamation. Gregory’s response was immediate and world-changing: he pronounced a sentence of excommunication and deposition against Henry IV. Never before had a Pope dared to depose a crowned head of state. This act was not only spiritual but political, as it dissolved the oaths of fealty that Henry’s subjects and vassal princes had sworn to him. The Emperor’s power base crumbled as German nobles seized the opportunity to rebel.

The most famous story of charity and spiritual authority from this period is the Road to Canossa. Facing a complete collapse of his empire, Henry IV was forced to seek absolution. In January 1077, he traveled to the remote castle of Canossa in the Apennine mountains, where Pope Gregory was staying. For three days, Henry, dressed only in a penitential sackcloth, stood barefoot in the snow, fasting and begging for the Pope’s forgiveness. Gregory, advised by Hugh of Cluny and Countess Matilda of Tuscany, eventually relented. This event was a profound, visible demonstration of the supremacy of spiritual power over temporal force—a story that forever fixed the image of the Papacy as the ultimate moral arbiter of the West. While Henry later rallied, invaded Rome, and installed an Antipope, the moral victory at Canossa permanently altered the relationship between Church and State.

The Teacher of Souls: Theological & Spiritual Legacy

The spiritual legacy of St. Gregory VII is rooted in a single, formidable concept: iustitia—divine righteousness or justice. For Gregory, justice was not merely a legal term but the active restoration of the Church to its God-intended, pure state, free from the contamination of worldly power. His core teaching was that the liberty of the Church (libertas Ecclesiae) was necessary for the salvation of the world. If the spiritual leaders were corrupt, how could the flock be saved?

His most direct theological and legal contribution is the enigmatic document known as the Dictatus Papae (1075). This list of twenty-seven succinct, declarative statements was likely not intended for public dissemination but served as an index of papal prerogatives compiled by Gregory or his chancery. These maxims represent the absolute maximum of his claims. Among the most startling are:

- That the Roman Pontiff alone can with right be called Universal. (Dictatus II)

- That he alone can depose and reinstate bishops. (Dictatus III)

- That it may be permitted to him to depose emperors. (Dictatus XII)

- That he may absolve subjects from their fealty to wicked men. (Dictatus XXVII)

These statements articulate the doctrine that the Pope is not merely the successor of St. Peter but the Vicar of Christ himself, holding direct authority from God to rule over spiritual and, when necessary for the Church’s protection, temporal affairs. This theory, fully elaborated by Gregory’s successors, became the foundation of the medieval papal monarchy.

Furthermore, Gregory was a powerful spiritual teacher through his extensive correspondence. His letters reveal a man of intense, almost mystical piety, who saw himself as a soldier fighting in a cosmic spiritual battle. He encouraged bishops and common Christians alike to pursue the vita apostolica, a life based on the simplicity, communal living, and poverty of the early apostles. For instance, he wrote to William the Conqueror, King of England, outlining the spiritual duties of a Christian ruler, but also reminding him of the ultimate hierarchy of heaven:

“Christ did not say to Peter, ‘You are an earthly king,’ but ‘You are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my Church.’ In this word, Christ committed the whole Church to his care, not just a corner of it. It is clear that the royal dignity, created by men who ignore God, is far beneath the dignity of the bishops, established by divine piety.”

He emphasized that the Church must be truly “one flock, one shepherd” (John 10:16), and he viewed his struggle against lay investiture as essential for the salvation of souls, not just a political power play. This deep, Christ-centered motivation is the enduring spiritual lesson of his pontificate.

The Via Dolorosa: Suffering, Death, and Sainthood

St. Gregory VII’s pontificate was an incessant Via Dolorosa—a way of the Cross—marked by relentless suffering, both political and personal. After the initial humiliation at Canossa, Henry IV regrouped and retaliated with fury. In 1084, the imperial forces captured Rome, and Henry installed his own appointee, the Antipope Clement III, forcing Gregory to take refuge in the heavily fortified Castel Sant’Angelo. It was a time of bitter spiritual dryness and intense political isolation.

In desperation, Gregory called upon his vassal, the Norman Duke Robert Guiscard, for rescue. Guiscard led his Norman army into Rome and successfully drove Henry IV out. However, the ensuing “rescue” turned into a catastrophic sacking of the city, far more destructive than the invasion by the Emperor. The Romans, horrified by the violence and pillaging committed by Gregory’s Norman allies, turned violently against the Pope. Forced to abandon the very city he had fought so hard to free, Gregory went into voluntary, yet painful, exile.

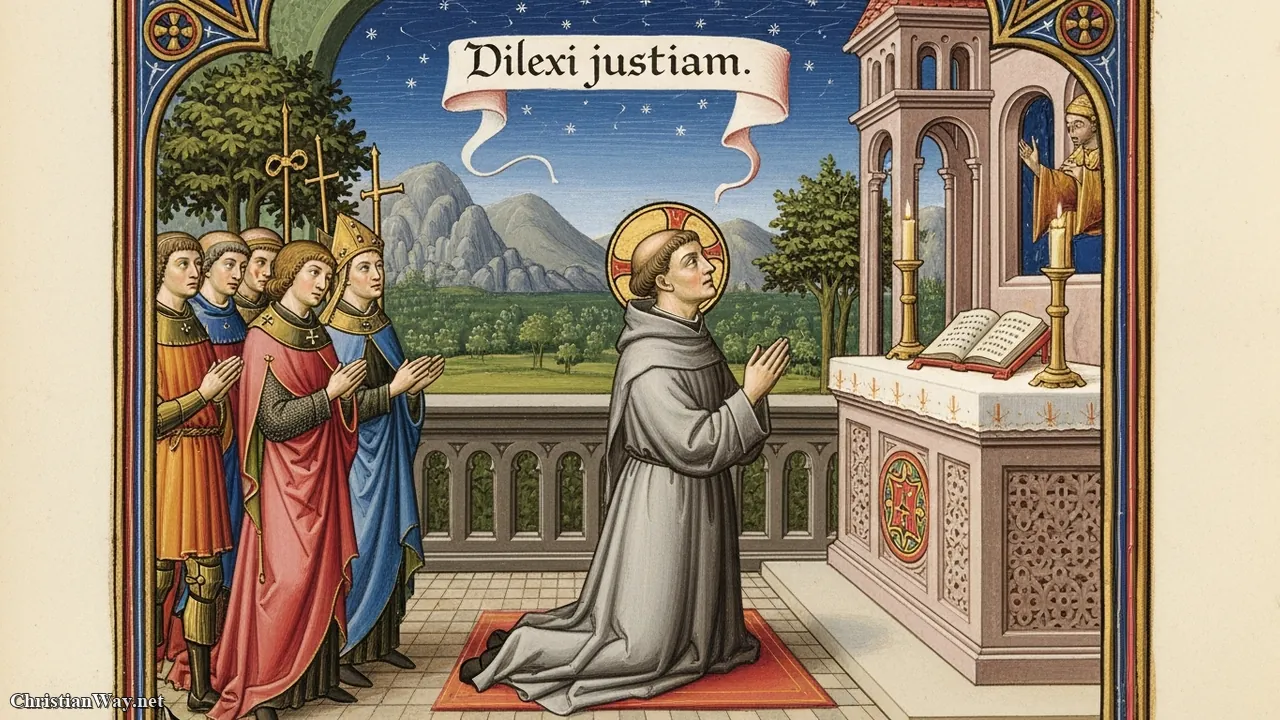

His final days were spent in Salerno, in the south of Italy. He was broken in body, having endured years of stress and illness, but his spirit remained unvanquished. On May 25, 1085, Pope Gregory VII died. His final words, a powerful adaptation of Psalm 45 (44):7, capture the entire tragedy and triumph of his life:

“Dilexi justitiam et odi iniquitatem, propterea morior in exilio.” (I have loved justice and hated iniquity, therefore I die in exile.)

He died, seemingly defeated and abandoned, yet the principles he championed proved victorious in the long run. His road to sainthood was slow due to the controversial nature of his confrontation with secular powers. The process began centuries later. He was beatified on May 25, 1584, by Pope Gregory XIII, a Pope who himself embodied the spirit of counter-reformation leadership. Finally, he was declared a Saint on May 24, 1728, by Pope Benedict XIII, who extended his veneration to the Universal Church. His memory continues to inspire the Church to stand firm against every encroachment of the world upon the spiritual realm.

Spiritual Highlights: Lessons for the Modern Christian

The life of St. Gregory VII is a tremendous reservoir of spiritual counsel for the Christian struggling in the tumultuous 21st century. Though his battles were fought with decrees and emperors, the underlying virtues remain timeless.

- Prioritize the Purity of the Church: He teaches us that institutional righteousness is a prerequisite for effective evangelization. We must first remove the “simony” of our own hearts—the pursuit of spiritual goods for worldly gain—before we can lead others.

- Practice Unflinching Courage: Gregory faced the most powerful man in the world and did not flinch, trusting in the authority gifted by Christ. We are called to stand courageously for the truth of the Gospel, even when facing powerful social or cultural opposition.

- Embrace the Vita Apostolica: He reminded the clergy to live simply and communally. For the lay faithful, this translates to renouncing consumerism and prioritizing the life of prayer and genuine community over isolating individualism.

- Integrity in Exile: His final words are the perfect response to perceived failure. True success is not measured by worldly victory or comfort, but by fidelity to justice. If fidelity leads to exile or suffering, so be it, for the reward is in heaven.

A Prayer for Intercession

O Almighty God, Who raised up Pope Saint Gregory VII to be an unflinching defender of Your holy Church against the corruption and pride of the world, grant us through his intercession a burning zeal for justice and an absolute dedication to the liberty of the Church. May we, like him, love righteousness and hate iniquity, accepting exile or hardship rather than compromising the truth of the Gospel. Protect Your Church from every worldly power that seeks to usurp Your divine authority, and inspire all Christians to courageously uphold the dignity of the spiritual life. Through Christ our Lord. Amen.

— Fr. John Matthew, for Christian Way